- Social and historical cultural identity

The landscape of the Galloway has been moulded and shaped over millions of years initiated by the gradual crumpling of the earth’s crust tectonic plates between what is now England pushing up the Lake District mountains and simultaneously forming Scotland’s Southern Uplands and the Solway flats between.

Subsequent ice ages’ glacial ebbing and flowing revealed the hard granite hills of Criffel, Cairnsmore of Fleet and Merrick while the soft red sandstone pockets in Dumfries and Lochmaben gave the region its future building materials and subsequent character and identity to the built form of its disparate towns, e.g. making Dalbeattie’s granite streets and Dumfries’ red sandstone townscape feel quite different.

The Southern Uplands are the southernmost and least populous of mainland Scotland's three major geographic areas. The term is used both to describe the geographical region and to collectively denote the various ranges of hills and mountains within this region. The scale and diversity of these Uplands creates a physical environment tricky to navigate except via its extensive coastline on the Solway Firth and on the rivers that flow south in the valleys between the ranges.

The Southern Upland Way path traverses all these ranges. The Southern Upland Way is Scotland's first and only official coast- to-coast long-distance route, running across the country from the Atlantic Ocean to the North Sea. From Portpatrick on the west coast the route runs to Cove and Cockburnspath on the east coast. The number of different accents found along the way is testament to the varied community identities not necessarily reflected by ad-hoc political or administrative boundaries but more by environmental domain and a specific place to belong.

An overwhelmingly rural and mainly agricultural region, the Southern Uplands is partly forested and contains many areas of open moorland. Galloway Forest Park alone covers an area of 777Km2.

- Historical + social backdrop - collective memory through buildings

This is not meant to be an exhaustive historical account of the region where the usually wealthy and significant personalities are trotted out, after all this is usually people who were either in the right place at the right time and events happened to them rather than having any meaningful personal qualities worth discussing in a project about a community regeneration project.

So, this is an interpretive appraisal to show why it matters to our project to learn from historical and cultural context and why it is important to weave this story in a meaningful and tangible way into our project.

Historical facts can be found in Dalbeattie Matters website and academic research. This document is an account of how history may have affected ordinary people through community events and buildings in the past.

- Timeline

10000 BCE the first immigrants’ remains found in Wales have recently been scientifically shown to be black skinned with blue eyes however this is only stated as it shifted culturally conditioned perceptions of our ancestors and our common DNA.

Local continuous habitation since 6000BCE is evidenced in the form of bronze and Iron Age community fortifications that can be found in the startlingly fluid stepped ramparts of Mote of Urr and the hidden Moyle in Dalbeattie Town Wood. These defensive places were usually near a water course and were capable of seeing off a siege by gathering food, livestock and the extended group behind a timber palisade in a common goal of survival. This would have promoted a sense of security and community; these structures were usually found on a strategic raised elevation, a symbol of longevity and certainty in a period of lawlessness.

Other smaller sentinel forts are scattered like stumps along the coast with defensible inland loch crannogs (timber piled structures) much like the rest of the coast of Scotland during this period of exploration for which the sea provided the highways.

- Brochs

Brochs are the most spectacular of a complex class of roundhouse buildings found throughout Atlantic Scotland. Think multi-storey, timber-framed crannog, then wrap in a dry- stone diaphragm wall of astonishing engineering conception.

The origin of brochs is a subject of continuing research. Sixty years ago most archaeologists believed that brochs, usually regarded as the 'castles' of Iron Age chieftains, were built by immigrants who had been pushed northward after being displaced first by the intrusions of Belgic tribes into what is now southeast England at the end of the second century BC and later by the Roman invasion of southern Britain beginning in AD 43.

Yet there is now little doubt that the hollow-walled broch tower was purely a unique creative invention particular to this Atlantic edge; even the kinds of pottery found inside them that most resembled south British styles were local hybrid forms. The precisely designed round form is redolent of modern cooling towers and was copied right up the Atlantic seaboard by presumably itinerant builders.

The distribution of brochs is centred on northern Scotland. Caithness, Sutherland and the Northern Isles have the densest concentrations, but there are a great many examples in the west of Scotland and the Hebrides. Although mainly concentrated in the northern Highlands and the Islands, a few examples occur in separately in south-west Scotland. This small group of southern brochs has never been satisfactorily explained.

- Candida Casa

The sea also made it possible for an exchange of skills, materials, and ideas and in the 5C Ninian reputedly built his Candida Casa (glittering house) at Whithorn. A Roman Scholar he brought back ideas from mainland Europe with a mission, presumably, to bring enlightenment to the superstitious paganistic Gallovidians.

The glittering house must have seemed magical indeed, drawing people like moths to a flame. The power of a simple building as a physical representation of ideas and meaning and a place of destination and pilgrimage is often underestimated.

Of course, like the rest of sea-faring Europe, others were on the move with various motives and the areas complex genetic mix is a result of Celtic Cumbrians, Romans, Angles, Irish, Scandinavians, et all and equally influenced language and place- name calling.

- Monasteries

Galloway was an autonomous territory from 1100 to 1300 and had a pivotal position in Irish Sea trade between England, Isle of Man, Ireland and Scotland during which time sophisticated land management ideas were introduced by the Cistercian Monastic way of life such as at New Abbey, Dundrennan, Glenluce, Kelso, and Melrose and this lasted until the late 1500’s when the Scottish Reformation caused the lands to fall to the crown and the monasteries fell into disuse.

The ideological Cistercians were systematic in agricultural methods, improved the land, and made sustainable agricultural changes that had a huge effect on the population as it relied heavily on a local workforce, providing a stable environment with both self-sufficient and exportable goods.

Dundrennan Abbey was constructed with robust grey sandstone and its form is noted for representing, in built form, the austere Cistercian ideal representing purity and restraint.

These monasteries were relatively sophisticated groupings of buildings with dormitories (a place to sleep), hospitals (a place to heal), refectories (a place to eat), libraries (a place to learn), kitchen gardens (a place to cultivate) an abbey (a place of community congregation) usually arranged around an ordering circulation idea like a cloister. The group would be carefully situated near a watercourse and a water supply would be piped to through the locations for various uses.

Technically these medieval buildings required skilled travelling immigrant European master craftsmen and masons who passed on skills and techniques to locals. They must have seemed truly fantastic creations to subsistence-living locals and be a tangible physical representation of community, well-being and hope.

New Abbey and Balliol College, Oxford was founded by Dervorguilla, wife of John de Balliol, and mother of John (born in Buittle Castle near Dalbeattie ) who was to become King of Scotland in 1292. This demonstrates the power and influence this Gallovidian family apparently had in Europe and not least the wealth they had accumulated. They were not inward looking and had a respected and credible place in international affairs.

- Tower Houses

History shows that the following War of Independence with England, in which Robert Bruce proved successful in Glen Trool, deep in what is now Galloway Forest Park, led to his cousin Edward Bruce becoming Lord of Galloway in the 14C. Robert never came back.

Buildings represented power and community investment in modest Tower Houses such as Buittle, Comlongon, Threave and Cardoness and sophisticated castle design such as at Caerlaverock with its triangular plan flourished between 12C and 17C. These robustly-built stone structures symbolise a different world from the monasteries, one of perpetual conflict and fear due to constant power struggles.

These Tower Houses are an evolution of the Brochs in the sense that the massively thick stone walls had secondary accommodation within such as staircases, a place to cook, a place to sleep, a place to sew and a place to read were carved out the solid leaving quite magical plans.

Notwithstanding that, Caerlaverock had a banqueting hall supported by a range of kitchens with the intention to provide social activities of a quality seen in the courts of London and would have a full range of storage facilities and accommodation to enable it to survive a lengthy siege. Like the mottes that expanded and added layers over time these castles adapted and evolved over the hundreds of years of continuous occupation.

- Witches and other innocents

The Reformation in the 16C and 17C was a period of conflict and easily shifted realignments of allegiances and in Galloway the Covenanters and Crown fought through “The Killing Times” of the late 17C with Covenanters’ martyrs’ graves witnessed in every Gallovidian graveyard.

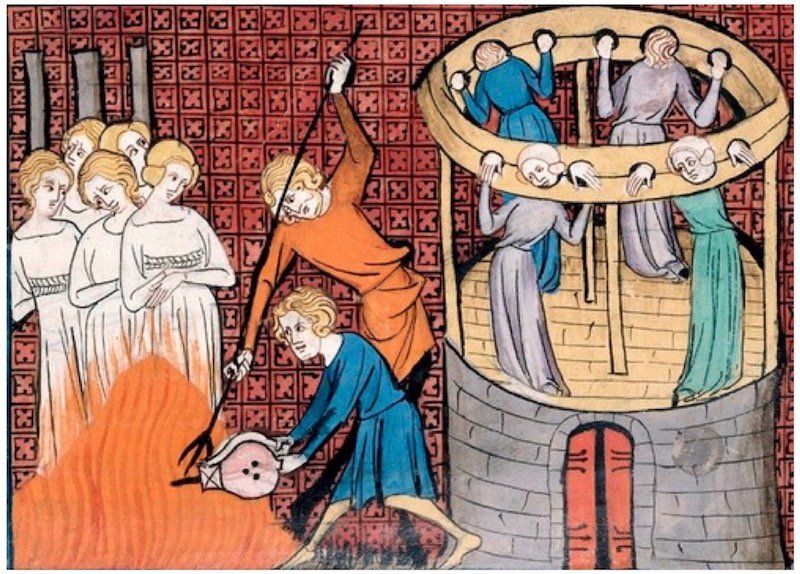

The common rural people were living in a time of extreme fear, not least from over-zealous Presbyterian fervour and as a consequence many innocent people were executed for being a “witch”. Elspeth McEwan from Balmaclellan was one of the last; however, witchcraft laws were not repealed till 1736. The three female Solway Martyrs, drowned at the stake for religious/political reasons, is a harrowing story of lunatic fanaticism and human courage, two well-known extremes of the human condition.

- Agrarian revolution

The Agrarian Revolution of the 18C saw the landowners of the region seek to transform the subsistence farming that had been reverted to once the monasteries had fallen. Communities in ferm-touns had infields (better) and outfields (rougher) that were divided into individually maintained run-rigs rather than the monastic efficiencies of scale. At this time there were no walls and cattle-droving created conflict as the herds moved from common-good ground across ferm-toun fields.

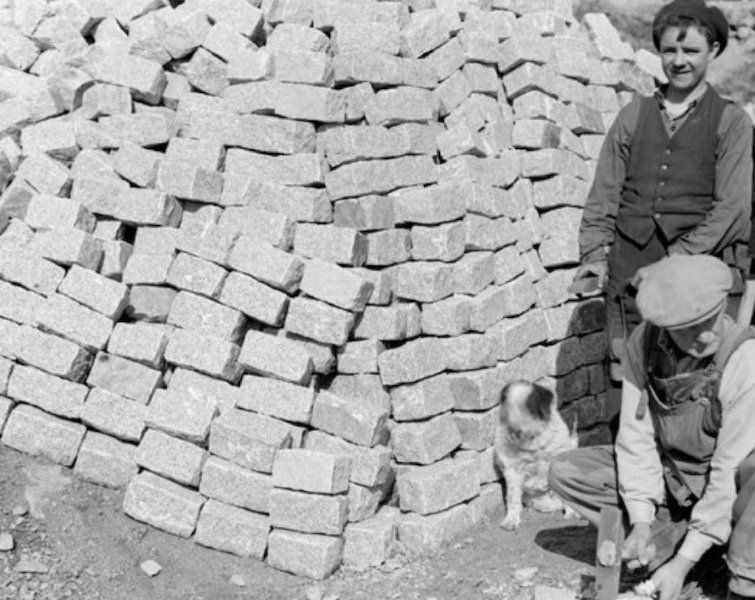

The improving landowners cleared the land of stones utilising this readily available material to create dry-stone dyking enclosures to protect crops and separate herds for controlling breeding and fattening for markets. The improvements also saw the introduction of new crop experimentation, drainage of sodden ground and fertilisation.

The legacy of the stone wall building programme 300 years ago can be seen all across the man-made landscape of Galloway with over 12000 linear kilometres recorded from the seaward raised beaches to the exposed moorlands and due to their distinctive construction methods with their through-stones at certain levels the walls have a character and identity unique to the place and the reflect the skilled hands of the itinerant labourers that built them.

The Galloway Hedge is a hybrid of drystone wall and blackthorn grown through it with the roots at the base of the wall binding the stones together making it a stronger and also providing wildlife habitat at the same time as being a windbreak. In today’s language an eco-friendly sustainable structure, a living wall.

Of course, all change comes with its detractors and The Levellers took the loss of common grazing and simultaneous notice to quit their tenant farms with the deserved contempt of a disenfranchised community by flattening as many of these walls as they could.

- Rocks to roads + lighthouses

Cynically motivated improvements did bring benefits for the majority in the form of road and bridge construction, designed for efficient mobilisation of troops to keep the oppressed rural communities in order, were gleefully utilised by the tax avoidance “export/import” entrepreneurs. The roads and bridges also connected communities and created markets, the power of which is not to be underestimated in a time of when people rarely interacted with another ferm-toun only 10km away.

Notwithstanding the impact new roads had, harbour infrastructure and boat trade was still a significant economic driver for the region with even Dalbeattie having a dock on the river Urr, Palnackie a river harbour for larger boats, Kippford had ship building yards, Carsethorn a pier for steam ship connection to Liverpool, even land-locked Gatehouse of Fleet built a canal to enable goods being loaded onto ships from the town at Port McAdam. Of course, Kirkcudbright and Garlieston still have working harbours albeit all were tidal.

The granite quarries of Creetown and Dalbeattie exploited being in proximity to the sea edge permitting the export of high quality granite to make the Stanley dock walls and granite setts at Liverpool and Eddystone Lighthouse, the Thames Embankment in London and robust lighthouses and harbours around the world.

Although much diminished the granite quarry industry still ticks over although the hand-working lathes and sett splitting tents of hard labour are long gone with material now used for road building substrate.

With new technology comes uncomfortable and exhilarating change and in the mid 19C the railway came to the region bringing tremendous economic growth whilst sounding the death knell for older industries. People moved on. New work was created, and opportunity saw ferm-touns grow into market towns and planned new towns.

- Industrial revolution

Inspirational industrial thinking ahead of its time (1917) is manifest in Tongland, a concrete framed multi-storey factory with brick and glass infill panels with factory precedents in Detroit, had, amongst other facilities, its own hydro-electric plant, workers’ swimming pool, a piano in the recreation area, and open-air tennis courts on the flat roof.

Almost entirely staffed by women due to a shortage of men away fighting in the First World War, the women were taken through aero-engineering apprenticeships demonstrating intelligence and application beyond any male counterparts and when the war ended the trained and skilled female workforce continued making cars specifically for other women called “The Galloway”.

This attracted the attention of the national suffragette movement and showcased feminist ideals. The building still stands as evidence of the creative thinking that brought all these new ideas together and today some are claiming this mix of work and leisure is somehow a new concept.

- Hello hydro

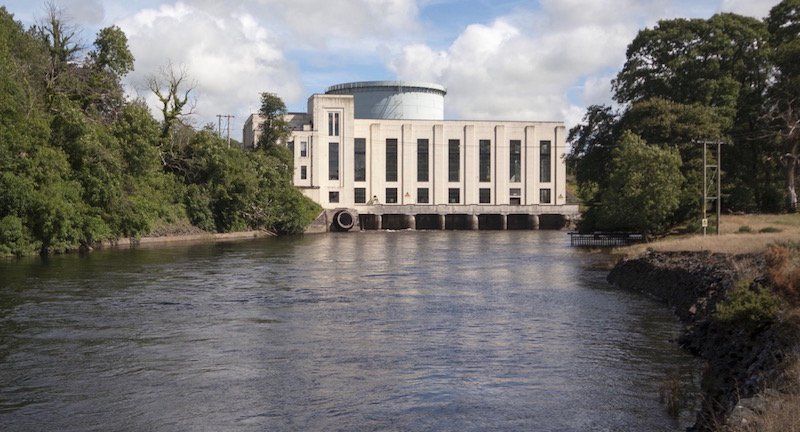

Hydro-electricity is a sustainable source of energy albeit with ecological issues of flooding valleys and river level control and Galloway has its fair share through a dam building programme in the 1930s. Serving the National Grid the facilities were not just a local utility.

Elegant concrete curved dams span between natural rock promontories with white modernist highly glazed buildings containing lofty and light filled turbine halls, a symbol of progressive ideas and new technology embracing international architectural modes. The electric palaces set in the countryside were held in high esteem by Gallovidians at the time, contemporary design representing a forward-thinking community outlook in a time of economic depression.

- Nitroglycerine

As we have seen from the mottes, castles and aero-engine factory conflict often generates new scenarios for land use and communities affected. During the Second World War a large munitions factory was established on the outskirts of Dalbeattie employing nearly 3000 labourers (living in work encampment) in a bid to construct the factory as quickly as possible. The site was chosen for environmental reasons with a requirement for a voluminous quantity of treated water, frost- free climate, and isolation from other industrial targets but connected with national infrastructure.

Located with access to the “Paddy Line” for its delivery of cordite and nitroglycerine and shipping of shells back to the front lines there were in fact two mirrored factories in case one was damaged either by accident or by enemy action.

Some buildings mimic the defensive motte shapes in that they were half buried under mounds of earth and grassed over giving them a pre-historic appearance. This was not to hide them from aerial attack but to direct any internal explosion vertically rather than a more catastrophic and destructive horizontal blast. Other resemble medieval defensive tower houses.

2,000 women from around the UK worked at the explosives factory, together with 200 men (mostly explosives scientists) and this had a big impact on accommodation in Dalbeattie, adjacent villages and towns and presumably created its own economy.

Local GP’s report that their experience was that women working with hazardous cordite and nitro-glycerine who remained in the area were later in life treated for symptoms directly related to this work.

These unsung women and men were instrumental in the war effort and are currently not acknowledged in any formal way, the only personal legacy being their graffiti etched into the factory walls.

- Intervia

In 1965, nearly 100 years after the bold concept of connecting rural communities with the railway, to enable economic growth, to connect national and international infrastructure, a short-sighted decision was taken to cut this umbilical cord and shut the “paddy line”.

Stations and their buildings are a symbol of an outward-looking mindset, status and connection with the wider community. Witness the economic power of re-opening the borders railway to Tweedbank to Edinburgh.

This environmentally smart transport system could now have been used to transport commercial shipping containers to the European Sea port terminal at Stranraer or even Cairnryan as the latter had its own railway connection during the Second World War. Unfortunately, the ubiquity of the car and the freedom it offers partly caused the trains to falter economically. The price for this lack of forethought puts unsustainable pressure on the roads and just calling the A75 a “Euro route” doesn’t change the detrimental effect the amount of international road shipping has on towns and communities. However, the Euro route A75 and its closeness to Dalbeattie offer the town a direct connection internationally for the car owner.

One health benefit of the south western railway redundancy has been the introduction of safe cycle-ways using some sections of the old tracks and viaducts through some particularly spectacular wilderness, unfortunately its full potential of a east-west path between Dumfries and Stranraer is not feasible due to its piecemeal selling-off of land, some simple joined-up strategic thinking could have created a continuous 75 mile long regional cycle route through the striking landscapes of the Southern Uplands, an economic equivalent of the West Highland Way. However, the sections that are available are easily reached for a Dalbeattie base.

- Farming culture

Galloway at one point changed its farming focus from beef to dairy to serve the industrial central belt with the railway ensuring fast fresh products reaching the demand efficiently. The creative technical development that sparked the Industrial Revolution wasn’t just reserved for heavy industries of ship- building and mining but mechanisation of the agricultural industry with such devices as the crop harvesters and milking machines meant specialist buildings and economies of scale turned farmers into process factories with science now playing as much a part as animal husbandry. Generic politically derived quotas are now driving economic and farming decisions and seemingly random closure of milk processing plants.

The various agricultural shows held throughout the region enable the exchange of ideas, technologies and skills, the bringing together fellow farmers and their families, sometimes a pursuit of often lonely endeavours and relentless timetables, so these temporary encampments allow the parades and demonstrations, a place to show off and relax. The regular livestock exchange markets bring together farmers under one roof, albeit in financial competition, also offer an opportunity to catch up with distant neighbours, a place to meet.

- Fishing culture

Fishing fleets have also waxed and waned with the traditional tidal river Haaf net fishing for salmon introduced by the Vikings all but extinct and with it a way of community life.

Fishing on open water has changed dramatically, restricted by political quotas and open sea stock sustainability the boat crews inextricably linked to the culture of the towns they are based in find themselves seeking work on the sea but now as maintenance crew for the off-shore wind farms.

No longer the fresh catch being brought in on the high tide to be unloaded by the quayside to the demanding screeches of seagulls with the consequent closure of fish processing plants.

- Forestry culture

Forestry is a sustainable industry that employs a huge range of different expertise and support industries. Processing factories require good infrastructure and connections with markets and this is at odds with the location of the majority of the plantations. The Beeching cuts that decimated rural railway connections erased the “Paddy Line” that runs through the Galloway Forest Park......

The equivalent of the Agricultural Show there are Forestry community festivals held with APF 2016 having 315 international exhibitors and over 22000 visitors a reflection of the importance the industry has.

As well as the big forestry processing plant at Dalbeattie there are numerous small light-industrial and service industry economies that have ebbed and flowed over the decades and continue to serve the region and Dalbeattie provides the workforce for this. The nature of this work typifies the inhabitants of Dalbeattie.

- Winds of change

Windfarm investment, both off-shore in the Solway Firth and extensively on land, has seen the development of a global economy industry and piecemeal token community benefit. Some communities have profited directly from amenity funds to varying degrees depending on the impact of the turbine fields however it is difficult to see how this industry contributes anything lasting to community culture.

Community Councils’ decide autonomously what to do with cash windfalls to varying degrees of effectiveness. Joined-up thinking here might create bigger more meaningful projects.

Unlike the 1930’s Hydro schemes the turbine fields have no buildings or structures that have the illusion of being occupied with busy workers.

The wind turbines seem like robotic elegant trees set mostly in a carpet of moorland connected by a tightrope of electrical wires disappearing off to the metropolitan areas. The shallow Solway Firth turbine blades animate and punctuate the horizon although with the firth’s tidal race would it not have been feasible to harness this in a hidden way too making the region experimentally self-sufficient in electricity, building on the bold ambitions of the Hydro projects of the 1930s

- Our futures

Dalbeattie has a stable population and a new learning Campus, does not suffer from the same second-home syndrome of neighbouring, arguably more picturesque, Kippford and Rockcliffe but is feeling the same effects of national High Street turmoil with all banks now having left the town.

Naturally, competing for commercial partners with neighbouring towns such as Castle Douglas, with its consequent angst created by supermarket economies and the onslaught of internet shopping, small rural Scottish towns are perpetually looking for ways to stabilise their economic position and encourage investment.

Tourism is seen by the Government as a key economic driver for the region’s economic development however, the region automatically competes with other regions and international visitors for unique, rewarding and fulfilling experiences and returning trade.

From this overview of a much abridged Historical, Social and Cultural context we have seen that identity and a community’s self-esteem can be reflected in the buildings and civic spaces that we inhabit as much as the work that we do to create an economy. The value of this social “return” is difficult to measure financially but nonetheless if designed well townscape contributes to wellbeing, identity and meaningful experience.

A pro-active attitude about healthy, active living, at grass roots level and from an early age for all degrees of physical and cognitive abilities should logically lower the financial burden on the NHS e.g., in other words small interventions can impact the wider community.

Iceberg

PHOTO: Jeremy Harbeck

Forest

PHOTO: Vinckie

Mote of Urr Etching

PHOTO: Roger Griffith

Mote of Urr

PHOTO: Tektonika

Broch

PHOTO: Tektonika

Dundrennan Abbey

PHOTO: Lorna Campbell

Cardoness

PHOTO: Tektonika

Threave

PHOTO: Tektonika