- Words and Stones: Thematic Proposal

To ‘interpret’ means ‘to give meaning to’. For humanity it is one of the most important things we do. We interpret the meaning of our lives in order to understand who we are, where we have come from, and where we might be going.

As artists and scientists, planners and managers, producers and consumers, we are all instinctive interpreters, seeking meaning wherever it is to be found.

In our surroundings, there are many places, buildings, objects and events that have a special meaning. Even the ordinary and everyday has meaning - usually hidden, sometimes surprising, but always relevant.

“The historic environment is a platform to stimulate citizenship and a sense of belonging”: extract from “our place in time” The Historic Environment Strategy for Scotland, 2014.

Dalbeattie Primary School having been established in 1876 following on the heels of so many other rural schools established as a consequence of the 1872 Education Act subsequently saw nearly 140 years of pupils pass through its glistening granite clad walls. The now redundant buildings undoubtedly have a special meaning in the community’s hearts and minds.

The History of Dalbeattie Primary School is recorded in a fine book of that name, a research project funded by Heritage Lottery ‘Sharing heritage’ Fund and William Heughan Associated Special trust in which information and memories are recorded.

This publication was prior to the exciting potential of the Asset Transfer of the site and buildings into community use.

Galloway’s history and cultural identity has local accents of a common Scottish story.

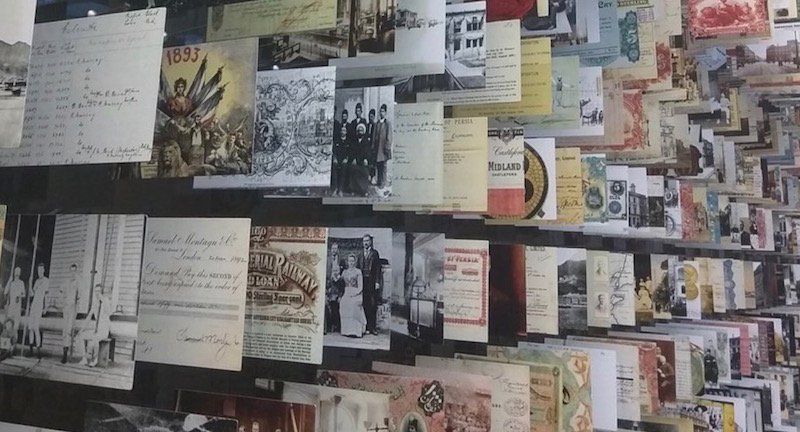

These national stories and artefacts can be found in collections such as the national Museum of Scotland and Museum of Rural Life albeit found in metropolitan conurbations.

The proposal is that the project interprets the untold story of the human interventions in the landscape of Galloway over time and the ordinary people who made them.

A story of invention, magic, conflict and oppression that is as relevant today as it was millennia ago.

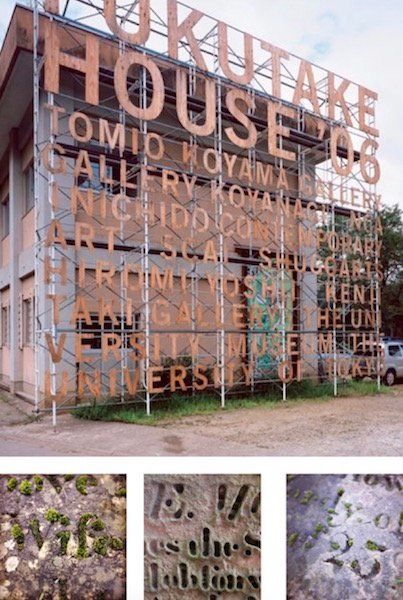

The proposal is for the Words and the Stones to be illustrated and illuminated both in the landscape and structures of the project, a public and social memorial that rewards curiosity and enquiry.

- Words and stones

So what to do and how to tell the story in the words and the stones, the ghosts of collective memory?

An idea, empathetic design and the use of writing techniques such as story-telling, humour and metaphor can make interpretation more effective.

Provoke, Relate, Reveal + Imagination is this discipline’s mantra.

Eyes on stalks, not bums on seats, to explore, probe, dissect, analyse and respond from many different angles in the most appropriate ways for this specific site, to experiment. Interpreting is so many things: finding out, expressing, uncovering, sharing, celebrating, giving different perspectives.

Italo Calvino, in ‘Invisible Cities’, asserts that “the grand challenge for art is to be capable of weaving together the various branches of knowledge, the different ‘codes’ into a manifold, multifaceted vision of the world.

The last thing we wish to do is dispel that sense of discovery that every new visitor scents on engaging with the project. Encourage further exploration.

Jean Piaget, child psychologist, notes that “you learn through inventing, not through being taught what others know but through experiencing, inventing knowledge anew”.

Unlike artificially-created experiences the school buildings are something precious, something unique - something real, that is what our visitors are coming to see - not the interpretation.

Interpretation is intended to move us, not ‘teach’ us, and most interpreters agree that the two are qualitatively different. A strong theme is one that provokes a person to think. When we are provoked by an idea, we think about it, wonder, ponder, and sometimes entertain new and wonderful possibilities about a place or thing or concept. This often results in implanting new beliefs about the thing being interpreted, or in existing beliefs being changed or replaced.

- Jaggy bushes

Give the people of Dalbeattie ownership and the opportunity to discover, create and communicate their own sense of the significance of a place through imaginative and emotional responses. Many remember the “refreshing” birthday treat ritual of being annually plunged into the playground jaggy bushes, something to look forward to!

Allow visitors to make their own meaning and connections with familiar objects, chosen by people like them rather than by curators. Since, in order for people to construct meaning, they must be able to connect it with what they already know, we have to accept that there is no one correct interpretation (the curatorial approach of museums fixed collections) and that people create their own knowledge and understanding from what is on display.

Interpretation can play a significant role in moving towards sustainable tourism. It is not just about economic return and visitor enjoyment, but also about making links between the visitor, the communities they visit and the heritage resource. This is crucial in the face of declining primary industries that are slowly waking up to the need to interpret their activities to the visiting urban dweller.

This can be better achieved through integration of how places are marketed, with the expectations of the visitor and the reality of what they find. Marketing, signage, and publications all link with interpretation and site management to enhance visitors’ experience, and to sustain heritage features and active communities. A total quality approach should apply just as much to the interpretation, as it does to accommodation and catering.

An audience, made up of unique individuals, has varying degrees of ability to read and understand. Many can find interpretation inaccessible, and it is essential we cater for all abilities and ages - and by doing so we will benefit a much wider audience. There are over one million adults with learning support - more than the number of wheel chair users. Like the rest of us, they have varied interests and many are seeking sources of inspiration for other pursuits such as art, music or drama.

There are certain “missing audiences” that are common to most, if not all, of the various sectors that make up our heritage. Included amongst these groups are the very young and the very old, people on low incomes, ethnic minorities, and in most sectors, rural communities. In other words, those commonly considered to be socially excluded.

It is clearly going to be crucial that the Arts are seen to stand alongside other areas of cultural expression, notably Historical and Environmental heritage. The chance to create work that inspires and reveals the unknown in an unexpected way is the real reward of commissioning an artist to work on an interpretation project.

This is ‘Experience based planning’, which aims to give visitors memories, not just ‘facts’ about heritage sites that they might otherwise forget. The visitor needs to believe that what they are experiencing still has an influence on them today and is not just a distant point in history. We aim to engage the visitor’s intellect and emotions on an equal level.

- Heritage Lottery Fund

Recent and current investments by the HLF require commitments to a wide range of benefits other than simply “preserving”, and it is in this context that they have taken an interest in interpretation. HLF are now funding very high-quality projects all chasing more limited funds and competition is very demanding.

Interpretation is best viewed in the context of HLF’s wider objectives. They are primarily a conservation organisation, so the starting point is that there has to be something – a tangible or intangible heritage asset – to conserve, in this case the school core buildings.

HLF have guidance on Access and Audience Development that is there to assist applicants in promoting this multiple approach to projects. Without that combination of benefits, they are unlikely to become involved.

HLF try hard not to get bogged down in defining heritage, they are determined that it is wide and inclusive. If we as a community can argue that a heritage asset, tangible or intangible, is important to us and your understanding of where we come from, then it meets HLF’s definition – it is our heritage.

HLF are aware that not all projects have tangible benefits in the form of a building, an exhibition or a book. Participation is itself a vital and potent benefit, particularly for new heritage audiences.

‘Markets of one’ and ‘mass customisation’, aim to develop more targeted interpretive programmes and services for a wider range of market groups. Interpretive planning is increasingly focusing on how to attract visitors, have them truly understand and remember our story and message, and at the same time get a return on our investment.

Interpretive planning must also address how the resource, the visitor, and the agencies /organisations will benefit from the interpretation.

- Thematic idea

The practice of commissioning artists has evolved from design competitions to the now more widely used approach of artist placements and residencies.

A critical factor in a successful artist commission is to create an environment where the artist can reveal an unknown insight. This environment needs to allow for the artist to research, probe and develop ideas in dialogue with the client. The outcome is probably not known at the start, so a working relationship based on trust is needed.

Without prejudice, we should be considering if the district’s wider historical and cultural story should be woven into the story of the school, with the school being a piece of the jigsaw rather than the whole.

We should also be considering this historical and cultural story’s relevance to the proposed use of the project and how it can be related rather than just superficial wallpaper.

Thematic interest can lift the story out of the dry historical book context and the thematic historical research carried out by the project team and outlined in the Consultant’s brief is suggested as being an embryonic staring point.

The theme of ordinary people and how they shaped the land and buildings over the centuries, oppressed by unstable politics and religious dogma, often unrecognised in historical accounts, is a story not commonly represented in museums and art galleries whose collections, normally commissioned or “gathered” by the wealthy, are held in secure established national museums immediately rendering them elitist.

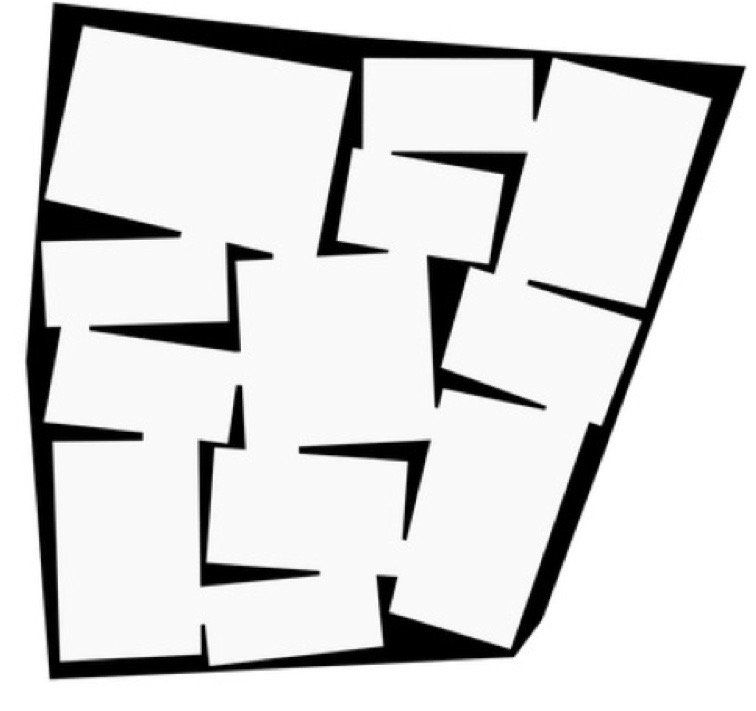

- Physical framework

It is proposed that the 77metres long new linear retaining wall that forms the new public square in front of the school bell tower represents a simple metaphor for the 777miles of drystone walls built by labourers who cleared the fields to improve the land. The diaphragm (777mm wide) retaining wall negotiates almost 7.7m of vertical drop and being adjacent the new natural amphitheatre for public gathering this will be a powerful canvas on which to “paint “the picture of ordinary people over time and be presented in the public domain, literally “art on the railings”, free to everyone to engage with.

At present the proposal is to make this “Memory Wall” out of Corten Steel, a material that the new core foyer is proposed to be clad in. This steel has a sacrificial coat of rust that then protects the material from further degradation, in itself metaphorical, and is a perfect contrast in colour and texture and factory process to the Craignair grey granite hewn for the hill, cut-outs from sheets rather than carved from solid.

The linear nature of the wall lends itself to a timeline frieze which could be laser cut out of the steel or formed in 3D from folding and pressing out shapes by local fabricators to any design.

Significantly this simple, but powerful wall, reaches directly out towards the wooded path leading to prehistoric motte of The Moyle in Dalbeattie Town Wood and at the other end into the 21C park of the future and the Motte of Urr at the top of the Urr valley encouraging exploration of the landscapes beyond, such as the 7 stanes trails and other wild routes.

This memory wall artefact and its related square, like the clock tower in the Glasgow Central Station concourse, would be a meeting point, for everyone: cyclists, walkers, orienteers, tourists, historians, families, clubs and like the clock be a springboard for exploratory journeys out into the landscape.

It seems that the wall’s public prominence in the project is an ideal blank canvas and that this could lead to smaller interventions in the buildings and the landscape.

There is also space for temporary exhibition in the education block however this is seen as a separate entity and not core to the “words and stones” story.

- Case Study 01: Kelvingrove

A new system of flexible ‘permanent’ displays has been developed and tested at Kelvingrove Art Gallery and Museum, the most visited British museum outside London. Like many Victorian Gothic museums, Kelvingrove is creaking at the joints.

The problem was that ‘permanent’ displays often end up with an inflexible rationale, theme and architecture. With a long gestation period for large projects, such displays can date quickly and need renewing a few years after completion. So is there an alternative? Our community and educational advisory panels, and a great deal of visitor research, suggested we should provide a range of experiences and cater for different learning styles - contemplative, hands-on, sad, stirring, fun etc.

However, if the public’s involvement in shaping the displays was going to be more than a one-off exercise, and we were to have the ability to incorporate new research, then displays simply had to be flexible - both physically and intellectually. As a one- off capital project, we wanted the new displays to be capable of change. To do this we had to abandon ideas of large linear narrative galleries that fix collections and interpretation, and instead focus on specific ‘stories’ that arise out of the objects and visitor interests.

These stories would be grouped within gallery themes chosen to reflect the strengths of the collection and visitor interest, and as an aid to orientation, rather than traditional academic themes. Thus both the ‘story displays’ and themes would change over time. Around 80% of the gallery space would be devoted to 120 story displays with 8 story changes each year. The rest of the display space would be devoted to four Discovery rooms: hands- on areas; a Display Study Centre; open storage with research facilities; and two Object Cinemas - son et Lumiere type displays mixing objects, light, sound and projection.

The first phase of a prototype flexible story display system has now been developed and evaluated, focusing on two ‘stories’ - ‘Introduction to Italian Renaissance Art’ and ‘St. Kilda: Living with the land’.

The idea was to create standardised modules that could be arranged in different ways that were capable of containing a mix of all likely objects and media, but could also accommodate bespoke finishes and graphics to avoid a ‘trade show‘ look.

The key modules were the case, table, bench, screen and slab. The idea has proved very popular, with over 75% of respondents in the evaluation rating the design of the displays as good or very good. The results of both the public and technical evaluation will inform a second phase of development and evaluation, to test additional elements and to refine the production brief, planned for March - April 2000.

- Case Study 02: Poems on the river Cree

A writer working with the landscape in a direct way can be very effective in bridging the gap between visual art and the written word. Nic Coombey of Solway Heritage and poet Liz Niven were commissioned by the Newton Stewart Initiative to research and write a series of poems that would reveal and emphasise the value of the surroundings and reveal the hidden history and ecology of the River Cree.

The connection between the river and people was especially important. Liz spoke to local people who use the river, and researched the town’s history and the river’s ecology. This information was distilled and filtered through her work. The bombardment of words, their sounds and rhythms were as important as hearing peoples’ ideas and opinions. The names of plants, animals and fishing flies frequently held a rhythm of their own or an echo of others. The words were incorporated into landmarks and elements along the route.

Liz and Solway Heritage worked with local crafts people to bring the words alive, and poems are now found embedded in many bridges, handrail and seats along the river. Accessibility was key to gaining ownership and understanding amongst the community. Liz, who lives locally, gained the trust of both the commissioner and viewers through her research and project development process. Her own work and aspirations also grew as a result, and now a new publication has been released. It is this two-way dialogue that allowed the interpretative role of both artists to develop beyond our expectations. I urge you to take a controlled risk, and to commission or become involved with an art project that has the ability to surprise and reveal the unknown.

- Case Study 03: Saying it without words

We respond differently to different forms of communication. Text based media can instruct us, but arts media and activities can help us to feel by connecting with us in a more affective (emotional) way. Here we present an Interpret Britain Award winning interpretive project in the Peak District. What are the three most important concepts in interpretation? No not Provoke, Relate, Reveal. Even more important than those are Communication, Communication and Communication. But communication is a two way process; it means listening as well as speaking.

The National Trust High Peak Estate in the Derbyshire Peak District is an area of outstanding ecological, archaeological, and geological significance. It is also a fabulous place for a day out. When we first set about devising an interpretation strategy for the property, we wanted to integrate interpretation into a wider learning plan involving staff, volunteers and the public where two-way communication plays a crucial role in the day to day management of the property. Arts activities are central to the provision of learning on the property. The combination of hands-on arts activities in a spectacular natural setting produces a double whammy of powerful personal involvement and emotional engagement which can lead to the sort of “life-changing experiences” that the new National Trust Learning Vision advocates.

When we had the opportunity to renovate an archaeologically significant vernacular farm building to be used as an interpretation shelter, we wanted to use arts media and involvement with a local school to shape both the process and the end result of the interpretation. Grindle Barn in the Upper Derwent Valley lies on an old packhorse trail and is now part of a farm which retains traditional hay meadows - so many of which have disappeared in the last 50 years. The importance of the farm’s history and wildlife make a visit doubly rewarding, but how could we go about communicating this hidden significance?

We started by commissioning artist Nicola Henshaw to carve a wooden bench which would symbolise some of the natural life of the area. The arms of the bench are in the shape of a curlew’s head with its long downward bending bill. The bench fulfils the practical needs of the visitor while also suggesting deeper layers of interest. We also commissioned Nicola to carve a wooden panel which would go above the doorway, showing a timeline of life in the valley from the monks of Welbeck Abbey who first introduced sheep onto the hills, to the packhorse trains of the 18th century, and the present day walkers and wildlife of the moors and fields.

The next stage was to work with the local school and two artists to collect natural and historical images of the area and rework them in clay to create ceramic tile pieces to be inlaid into the barn walls. Children from Bamford School visited the barn and by means of a role-play we recreated the life of the packhorse trains, investigating how and why the landscape has changed over the centuries. Artists Lesley Fallais and Les Biggs worked with the children collecting words and images that reflected their understanding and response to this place. Back in school these images were added to and refined, with each child creating their own tile. The art work became part of the interpretive process allowing the individual to communicate their own response to and develop their own understanding of the place. They therefore created their own significance rather than have someone else’s significance forced on them. The only words on the barn walls are the words of one girl’s poem intended to evoke an emotional response. For the rest visitors can see dotted around the walls small images on the ceramic tiles that refer to the life, past and present, of this place. If they are sufficiently intrigued to find out more there is a leaflet, illustrated by the children, available in a dispenser in the barn.

This provides more information in the form of an imaginative journey of a packhorse train through a changing landscape, identification of some of the hay meadow flowers, information about the environmental significance of this site, and useful visitor information.

Grindle Barn demonstrates an arts based approach to interpretation and learning across the property that gives people the opportunity to discover, create and communicate their own sense of the significance of a place through imaginative and emotional responses. In making the Interpret Britain award, the judge noted that they were “particularly impressed by the integration of arts activities as a medium for interpretation...the interpretation appealed not just on an intellectual level but also on an emotional level, encouraging a response and direct involvement from the user.”

Adrian Tissier, The National Trust adrian.tissier@nationaltrust.org.uk

- Case Study 04: Land marking

Many of us respond to the landscape with passion. It takes an artist’s vision and skills to communicate that feeling coherently. Sculptor, John Behm’s response to his local landscape are his Waymerks on the Southern Upland Way. The footpath passes John’s studio. Its walkers know nothing of the struggles of the artist within, so John was inspired to champion the tradition of making.

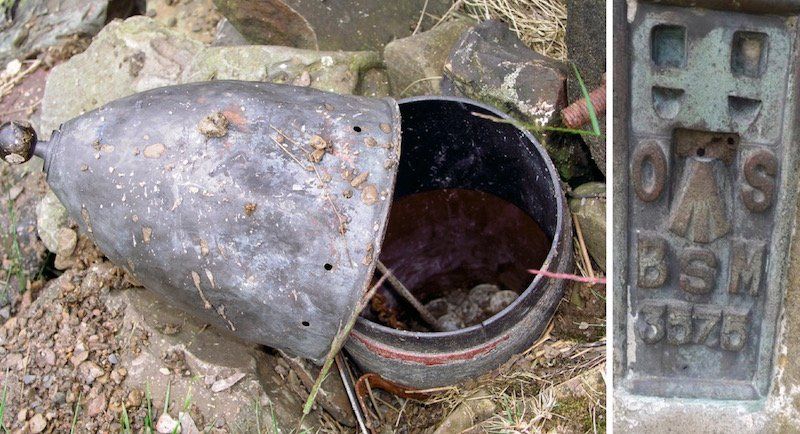

Calling on his knowledge of history and archaeology, he thought out a way to draw attention to the rich products of past makers: the artefacts that bear witness to their craftsmanship, ingenuity and sense of design. He sought to demonstrate that artists still make beautiful things, and to remind people of the rich wildlife, past and present. Hand-minted in lead and copper, the Waymerks are ‘art tokens’. There are thirteen reverse designs, for thirteen stages of the footpath, and a common obverse. The latter is a palimpsest of earthworks which suggest mankind’s impact on the landscape. A Bronze Age beaker, an Iron Age sickle with a phallic handle, and an Anglo-Saxon beast from a ring are represented on the Waymerks. A wild boar appears for the Melrose section of the walk. This has double resonance: not only a former resident, it was also the insignia of the XX Legion at nearby Trimontium. The Waymerks are left in hoards in artist-made kists. These have been concealed, though never completely buried, at remote and lovely places along the Way.

Walkers are invited to take to the hills and look for them. Bronze plaques (bearing a bastard Latin word ULTREIA (‘on with your quest’) on the waymarker either side of the kist site identify where to look. Successful hunters take home a Waymerk. The response of walkers has been delight, sometimes rhapsody. “I adored the submerged basin with its lid bearing the Covenantor text, but nothing can match that cunning little stone drawer in the bank!” wrote one. People report that they do go home and look at the website (www.waymerks.org.uk) written on every kist to discover the background to the designs. Many who have found a kist by chance say they have returned to the Way to search for others. The lure of an art-treasure hunt has people out on the hills, appreciating not only the landscape but the creativity of the people who live on it now and who have done so in the past.

Fi Martynoga is an arts organiser and environmentalist who manages the Waymerks project: fi@martynoga.freeserve.co.uk

- Case Study 05: Process

I should start by introducing myself as a ‘process-led’ artist.

This little piece of artworld jargon means that I have no loyalty to any particular medium: instead I work by immersing myself within a situation or place through a process of multi- layered research. Out of this I this create an artwork entirely specific to the place.

‘The context is half the work’ is the mantra of much site-specific art practice, meaning that the artwork cannot exist separately from its surroundings. It derives its power from the web of relationships between the place and the artist’s intervention in or with that place. When considering artworks as a part of interpretation practice, this relationship is particularly pertinent. An artwork is by definition subjective and will therefore contain many layers of potential interpretation; in order to achieve this within a contextual work it is necessary for the artist to understand a place as a multileveled entity.

Experience: My research begins with direct experience, spending time alone in a place, sensing an intuitive response. Often this will take the form of an idea of scale, a characterisation in terms of texture (hard/soft, stable/mobile, loud/quiet etc) and a relationship to surrounding features (buildings, landforms etc). The intuitive response is then a foundation of the work and crucially the sounding board against which all further research is tested.

Information: The second research phase is a gathering of factual, anecdotal and experiential information about the place. Much time is spent walking in and about the place and speaking to people connected with it (a place exists as the sum of the thoughts of those who live there, those who used to live there, those who have visited and those who have never been there). These conversations form another key foundation to the work; a mixture of personal anecdote, history, opinion and conjecture. More often than not each conversation will throw up more suggestions of people to talk to: following this seemingly random sequence can uncover a chance remark or story that becomes an essential generator for the work. Alongside this work is a similarly chance-informed trail through maps, text and images related to the place.

Experiment: At this point in the process the work has begun to suggest a material form, and the third stage of research usually starts in the studio with experiments with materials and imagery. Materiality, and the technology inherent in shaping and joining materials, are fundamental to the reading of the work and often an idea demands research into unfamiliar processes or design precedents: for example a recent project led me into working with the artificial sea used by the wave energy research group at Edinburgh University to test the buoyancy and movement characteristics of a floating section of an artwork.

Observation: The final aspect of research in my work is to consider each work as an experiment in its own right. As I see the purpose of my work being to contribute to the changing identity of a place, I assess the evolving relationship of a work to its context. Often this is impossible to assess through my own observation; instead I rely on a process of hearsay and observation from a distance (there is often nothing less helpful than the comment of someone made in the knowledge that they are talking to ‘the artist’). Often the way a work enters into the mythology of a place can take unexpected and frankly bizarre forms.

A suspended bronze figure that I made in Glasgow’s Gorbals began to seep a ruddy liquid from the centre of her outstretched palm: in a predominantly Catholic area this was rapidly passed round as a miracle (with a bit of a Glaswegian twinkle). The result was that I fulfilled a long cherished personal ambition of being featured in The News of the World , while the sculpture figured on several esoteric websites as a harbinger of the second coming of Jesus Christ! Probably more significantly, the episode has contributed to widespread local adoption of the artwork as a good luck charm for the neighbourhood. It is this kind of experience that informs my approach to practice, a practice that in its entirety can be seen as a process of research into the role of identity and memory in public space.

- What’s the point of people?

Can any of the following be measured or even answered?

An interpretive plan can be a vital part of the process of producing an accurate business plan and, hopefully, a successful funding application.

We have clearly stated the heritage merit of the project.

Keep the visitor experience in mind when developing interpretation.

Set clear, measurable interpretive objectives.

Ensure that the design brief follows on from the objectives of the interpretive plan. Ensure that the interpretation meets relevant national standards and best practice. Only take interpretive approaches that are practical to maintain.

Provide plans for ongoing development and refreshment.

Who are our visitors? School parties and family groups, parents and toddlers, retired people, office workers at lunchtime, specialist groups, coach parties, walkers. What they want to know and how they want to find out will vary enormously.

Where do they come from? Our visitors are local, from elsewhere in the UK, and from overseas. Many speak another language, we should consider translating some of our materials.

We have lots of repeat visitors who may appreciate a regular change in our interpretation or if abstract, reveal further connections in landscape.

Why do they visit? What are their motivations? Does what we provide meet their expectations and can we cater to all their interests? We need to be sure that the answers we offer match the questions they bring with them.

How long do visitors stay and what holds their interest the longest? Are there particular areas or tools that people seem most drawn to?

What level of knowledge do they bring with them? Are our visitors already experts in the subject we are interpreting, or is it likely to be something new to them? Understanding this will help us provide the appropriate content.

What are their physical and learning needs? Everyone has different access requirements and preferences for the way we gather information. It’s useful to bear in mind that the kind of interpretation we might enjoy will not be shared by everyone.

Who isn’t visiting and why? This is perhaps the most challenging question to answer, but one which is crucial if we are to encourage new visitors and broaden the appeal of our interpretation.

Stone Boat

PHOTO: Gryffinder

Dalbeattie Primary School

PHOTO: Dalbeattie Museum

Primary School Pupils

PHOTO: Dalbeattie Museum

Crowd

PHOTO: PD-Art